*WARNING: Flashing Colors*

IDM240: Interactive Graphics

By Jordan Zagerman – 2018

*WARNING: Flashing Colors*

IDM240: Interactive Graphics

By Jordan Zagerman – 2018

IDM362: Interactive App Design II by Seamus Donaldson

“Quote of the Day” is a concept I came up with for my Interactive App Design course. Since this was my first time experimenting with apples integrated development environment, Xcode, I knew I wanted to create something simple so that I could focus on learning the basics. The concept for Quote of the Day came to me after seeing an inspirational quote on Facebook; my idea was to show users inspirational quotes every day from influential people on their birthdays, thus Quote of the Day was created.

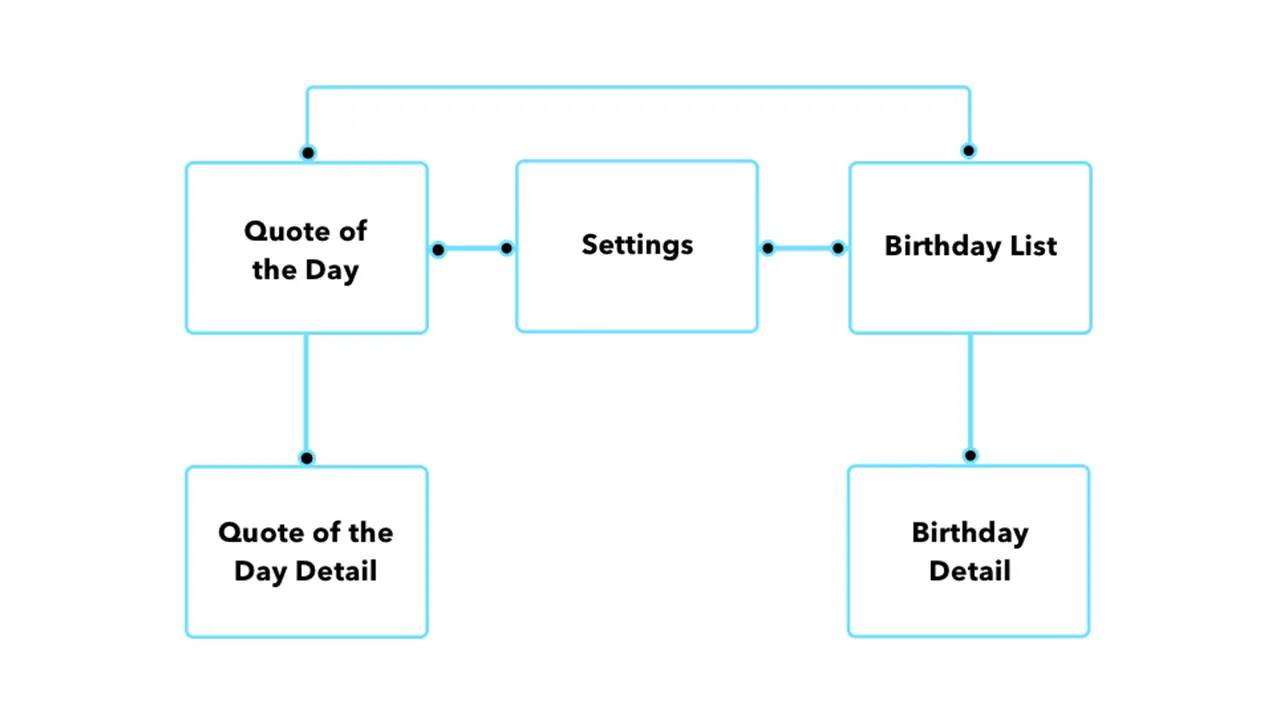

Once I had the idea for my app I needed to organize the content I wanted to include in a way that would make things easily accessible and user friendly. By creating a sitemap, I was able to clearly understand how users would get through the flow of the app. My goal was to make all pages accessible with just two taps.

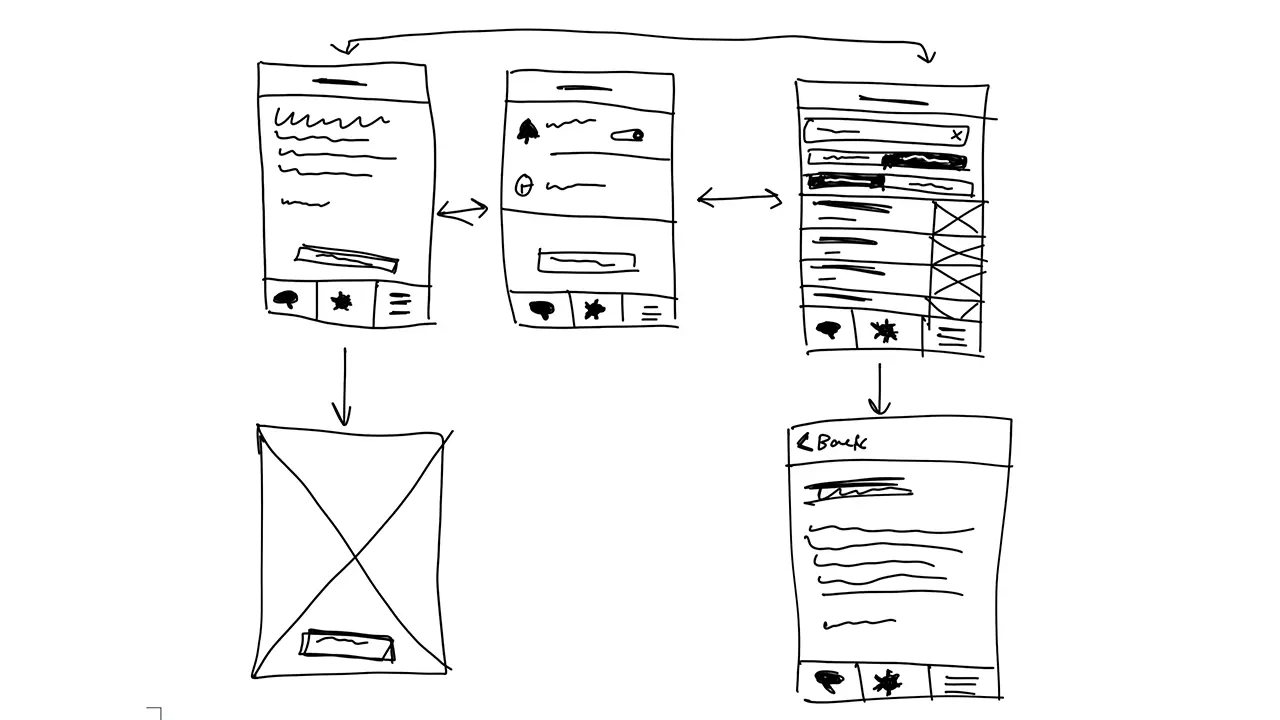

Before I could start designing my screens in Xcode I had to come up with some sketches that I could refer back to throughout development. I wanted the screens to be clean and free of all unnecessary content so I made sure to only include functional elements.

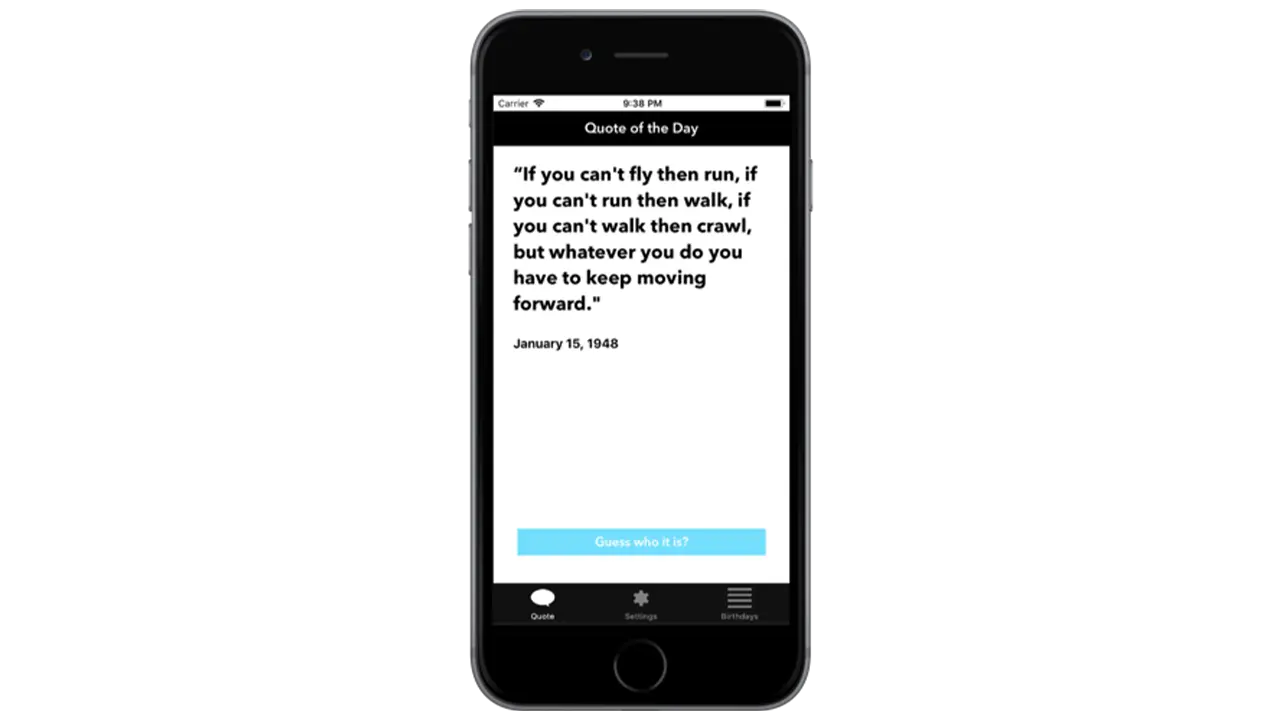

The first page I wanted people to see when opening up the app was the ‘Quote of the Day’. This is the primary function of the app so it made sense to show people the relevant quote of the day first. To make it a little more interesting I left out the name and picture of the person who’s being quoted so users could guess. Once a user had an idea, or just wanted to know who the quote came from, they could simply click ‘Guess who it is’ and the page would flip, showing the full portrait of the person as well as their name.

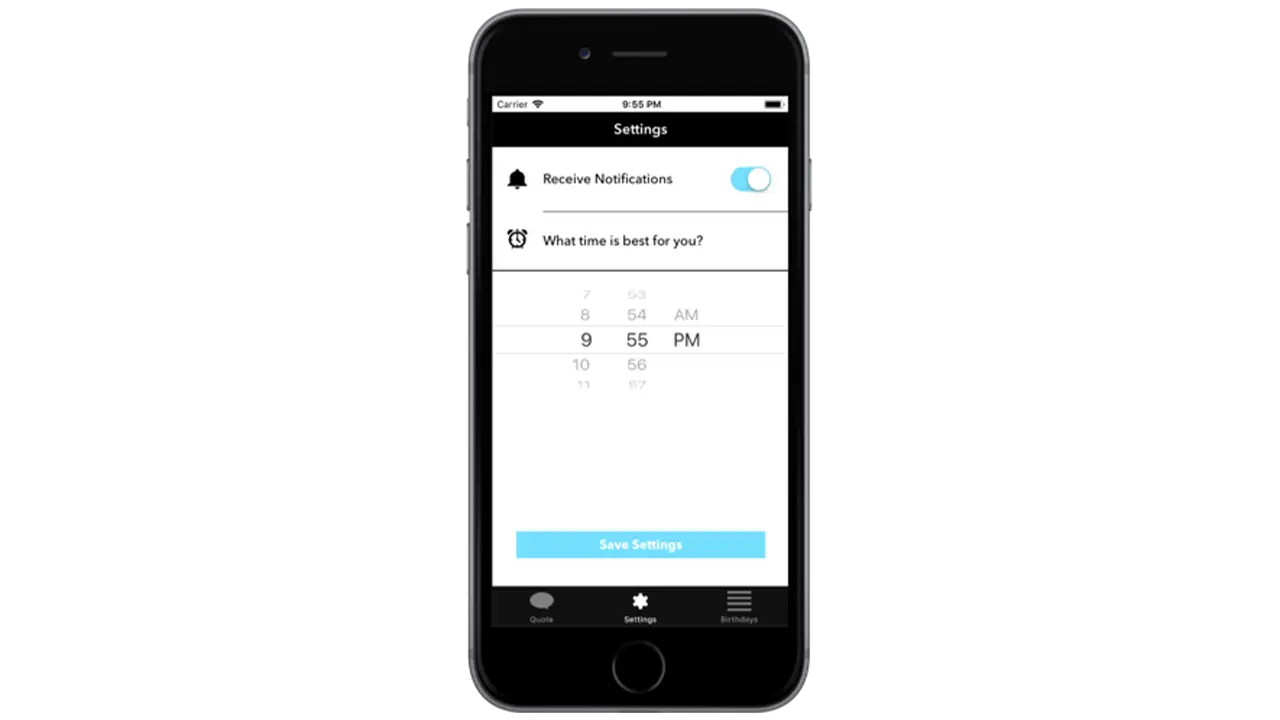

The settings page isn’t very interesting but when you’re creating a native app that takes advantage of notifications, it’s important to provide users with options for when they want to receive them, if at all. By simply asking users if and when they want to receive the notification for the quote of the day, I was able to create a clean and easy to understand interface that took advantage of premade elements in Xcode.

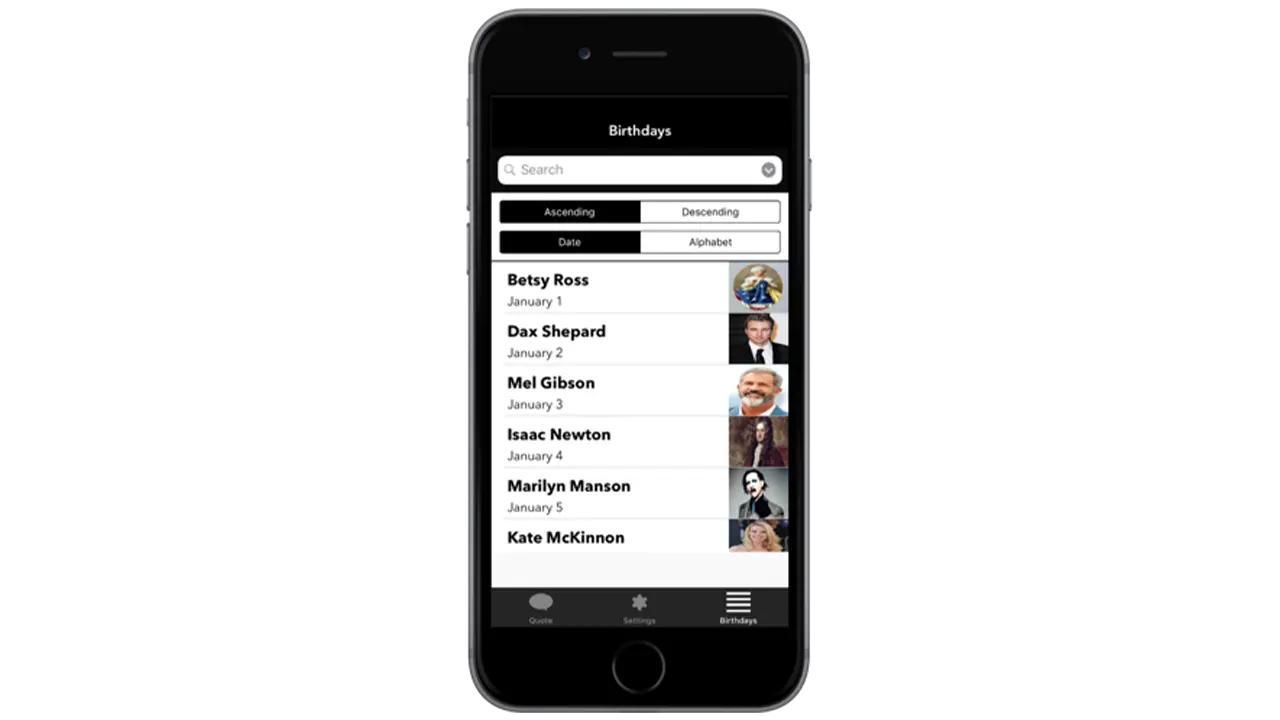

The birthday listing page is the secondary function of the app which is why it’s not the first page you see. If a user is curious to see more quotes they can go to the birthday listing page to see who’s featured on the app, and if they’re interested in seeing that persons quote, they can simply tap on their cell block and go to a detailed page that shows their quote.

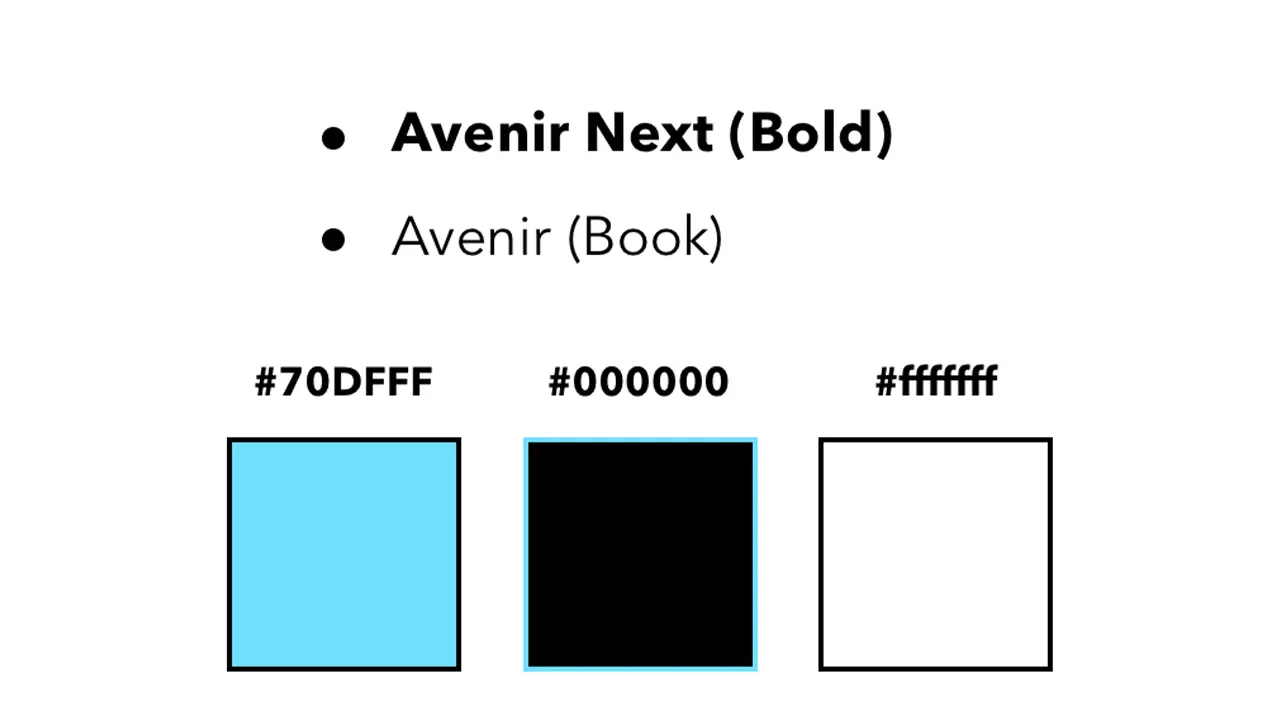

I wanted the aesthetic of the app to feel modern and sleek which is why I chose a black and white color scheme complimented by blue to represent functional buttons. I used Avenir next and regular because they’re both sans serif fonts and are easily readable.

All assets were created using Illustrator and Sketch. This included custom icons used throughout the app as well as the app icon. All images featuring influential people were edited in Photoshop to share equal proportions. The app was styled using Xcodes premade elements and constraints, and was then made functional using Swift.

To conclude, I’d first say, this was an awesome learning experience and definitely something I’d do again. Working in Xcode was not nearly as difficult as I thought it would be, and given that I’m very interested in app design, it’s a relief knowing I’ve got some experience under my belt. For the future, I’d try and get some more of my functionality down, but for now I am satisfied with what I’ve created.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is the single largest contributing factor to global climate change. If CO2 was black, together as a society, we would have taken strides to reduce it years ago.

Our solution to this problem was to create a way for people to view the world around them as if CO2 was visible, and give people achievable tasks that would help reduce their carbon footprint. It is easy to believe that your actions as an individual have no impact, but we wanted to show users that even something as small as turning off the lights when you leave a room can make a huge impact over time.

By repeating agile development sprints of research, prototyping, and testing over the course of IDM junior workshop, we achieved our goal of creating an AR app that raise awareness of the CO2 emissions in Philadelphia and ultimately made people more conscious of the impact of their carbon footprint.

Our first task was research. We needed to get each team member familiarized with CO2 and its impact on the environment. As we gained fundamental knowledge of the issue, we identified it as good problem to solve with augmented reality, being that CO2 is everywhere in the environment around you. With a strict 6 month timeline we decided for the sake of scope to focus on Philadelphia because of the ability to make an impact within our city.

With basic project scope outlined, we assigned general roles, Brendan Luu as team manager, Martina Calluori, Jacob Culp, Erin Wiegman, and Brendan Russo would focus on augmented reality development, and Tri Do would focus on design, with all team members helping out in different departments as needed.

Our final task before diving into our design sprints was getting familiar with Unity, a game engine that we were all using for the first time and also learning the pipeline of augmented reality development in Unity with Apple’s ARKit framework.

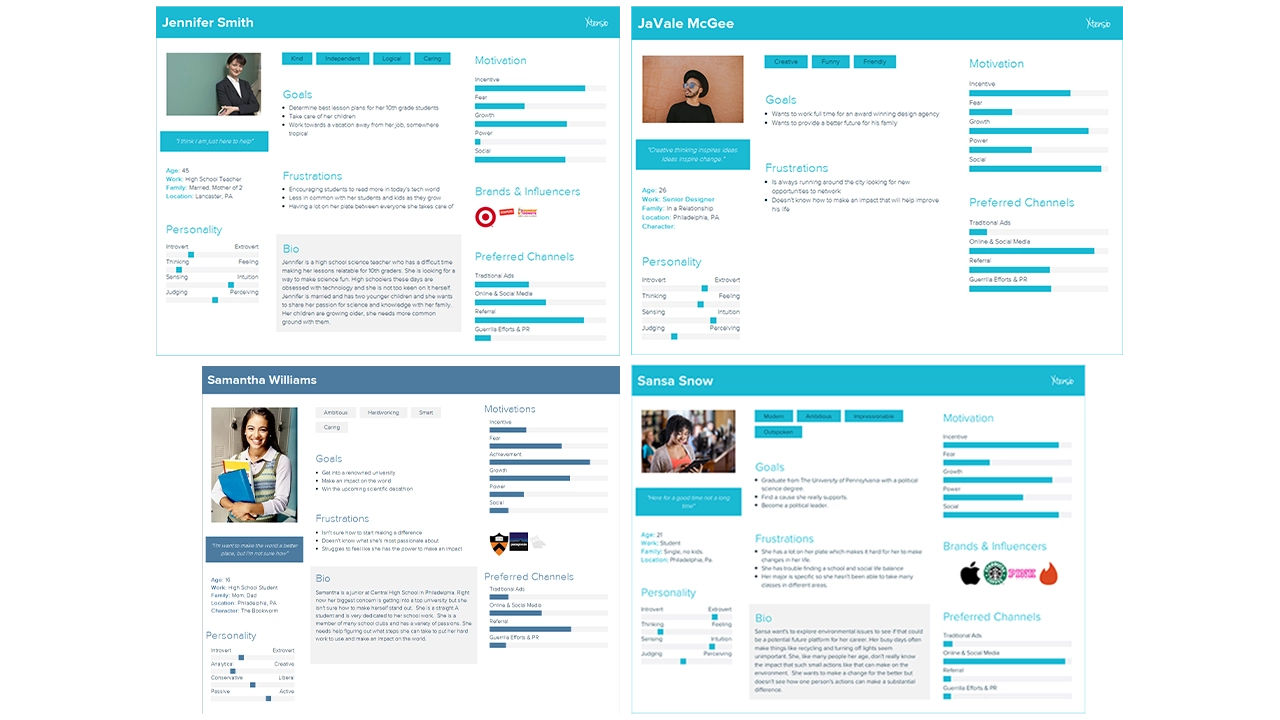

Our first design sprint started by defining our target audience, students primarily in the high school and college age range (15-22). We identified this age range because students are typically the most open to change and learning, and their changes would have the largest impact over their lifetime. We created user persona’s based on interviews we had with students in Philadelphia that fit into our target audience so we could easily picture actual people using our app rather than a number representing an age range.

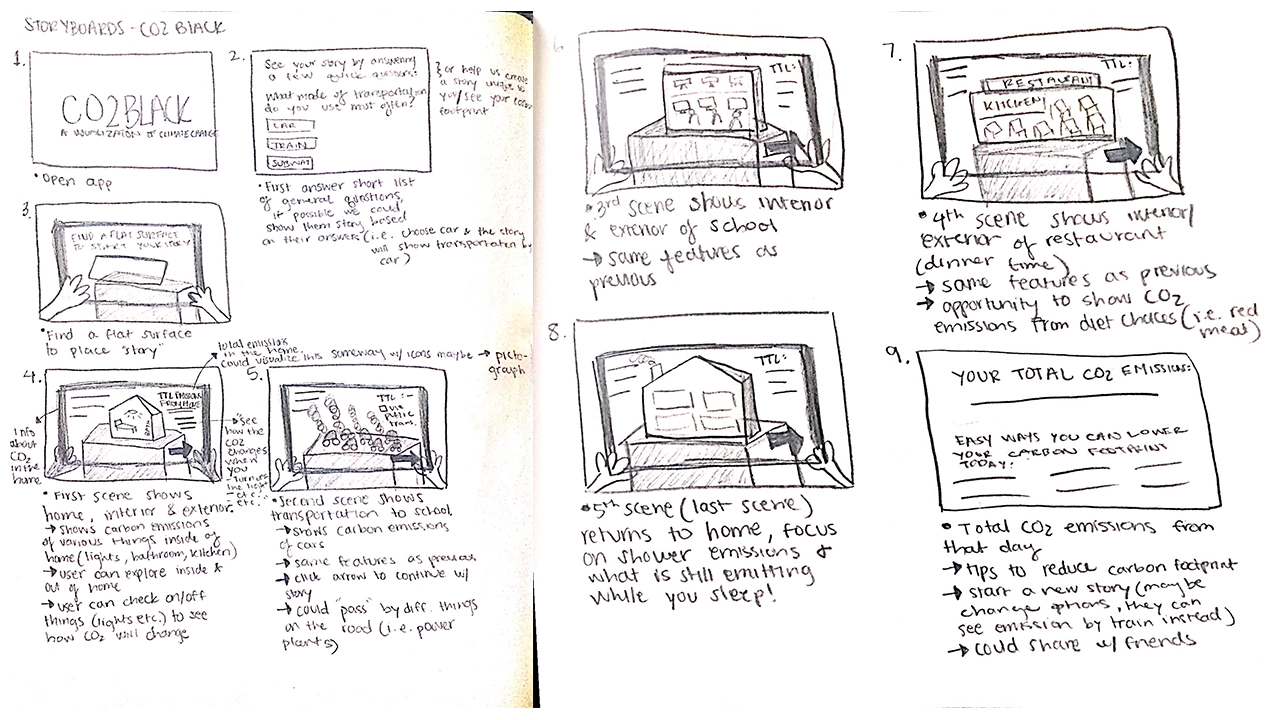

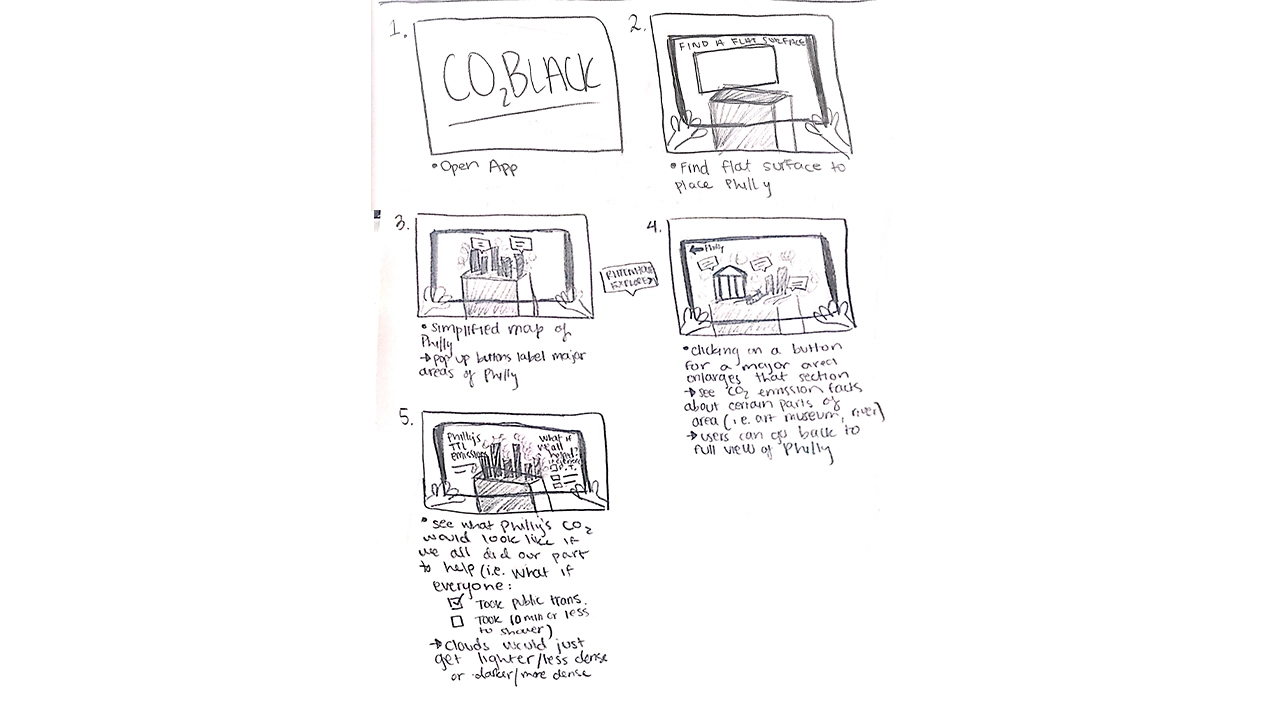

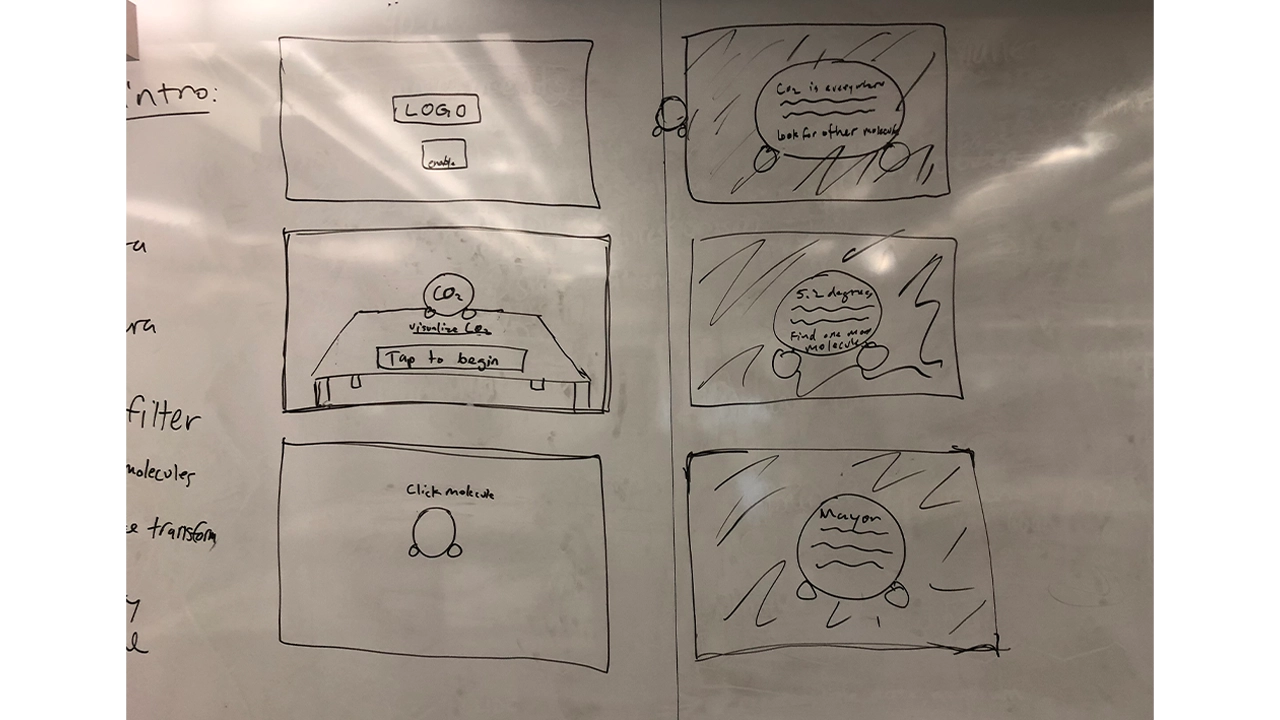

We then conceptualized storyboards to outline our vision for the app. Our first iteration started off with people navigating through dark clouds that represented CO2 and reading facts off of 3D models of CO2 molecules that were scattered around them. The second half of the experience allowed the user visualize CO2 in a completely different way by showing a miniature 3D map of Philadelphia being filled to the top with the dark smoke to show the smoke on a larger scale. Before getting into development, we wanted to see how people would interact with this new environment.

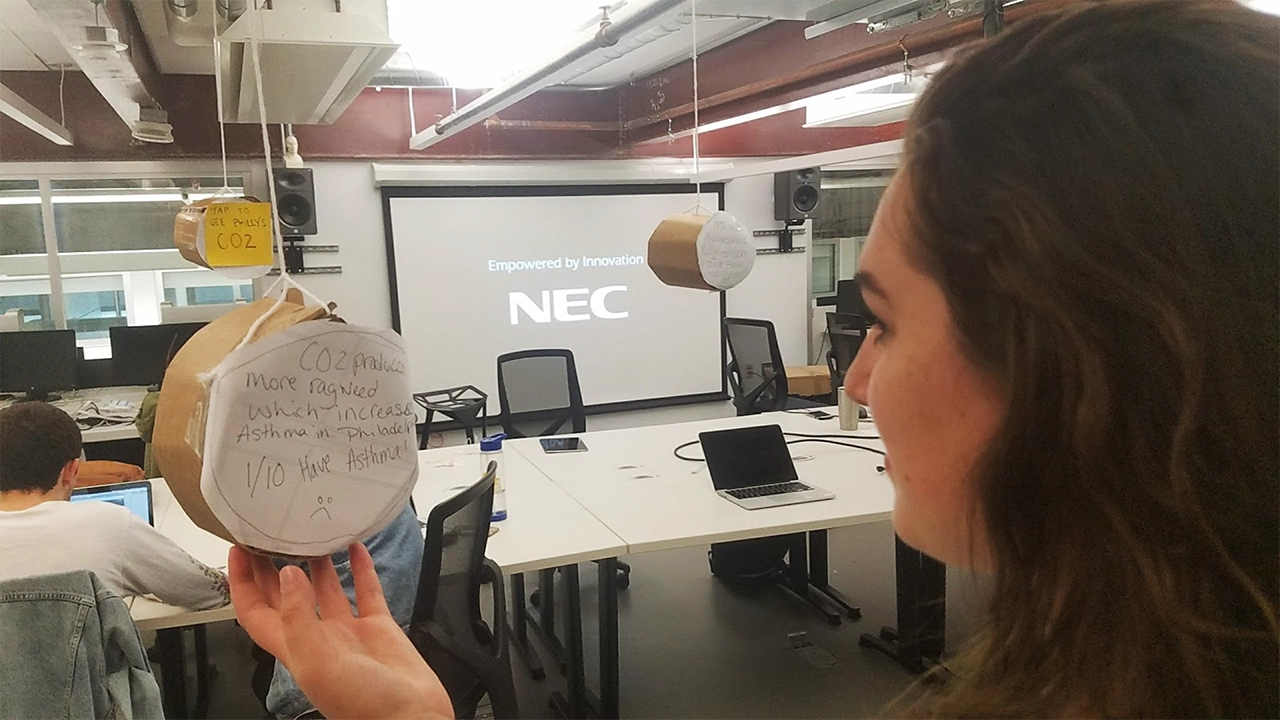

To test this, we build all components of the storyboard with cardboard, tape, and paper and took photos of each step and put that into a clickable prototype and presented this prototype on a phone to users for usability testing. This new way of prototyping in for AR was a good idea, but was not entirely successful because users did not feel like this was representing augmented reality, and it felt just like clicking through photos. We realized that for future projects we would still build the prototype with cardboard, but instead of having users click through a prototype we would bring them into the room where the cardboard experience is being displayed and have them actually navigate around the room and see how they would interact with that.

Based on feedback from the cardboard usability testing, we went forward with creating a low fidelity prototype of this experience. We created the Carbon Dioxide molecules and displayed facts in a text format on them, but users struggled to read the text in AR, there were too many representations of CO2 which left users confused, and users didn’t know what to do with these facts and newly acquired information. We surveyed more people in our target audience and realized that we were approaching the problem all wrong, and shifted our focus to giving people achievable tasks, and making the data more geared towards the individual.

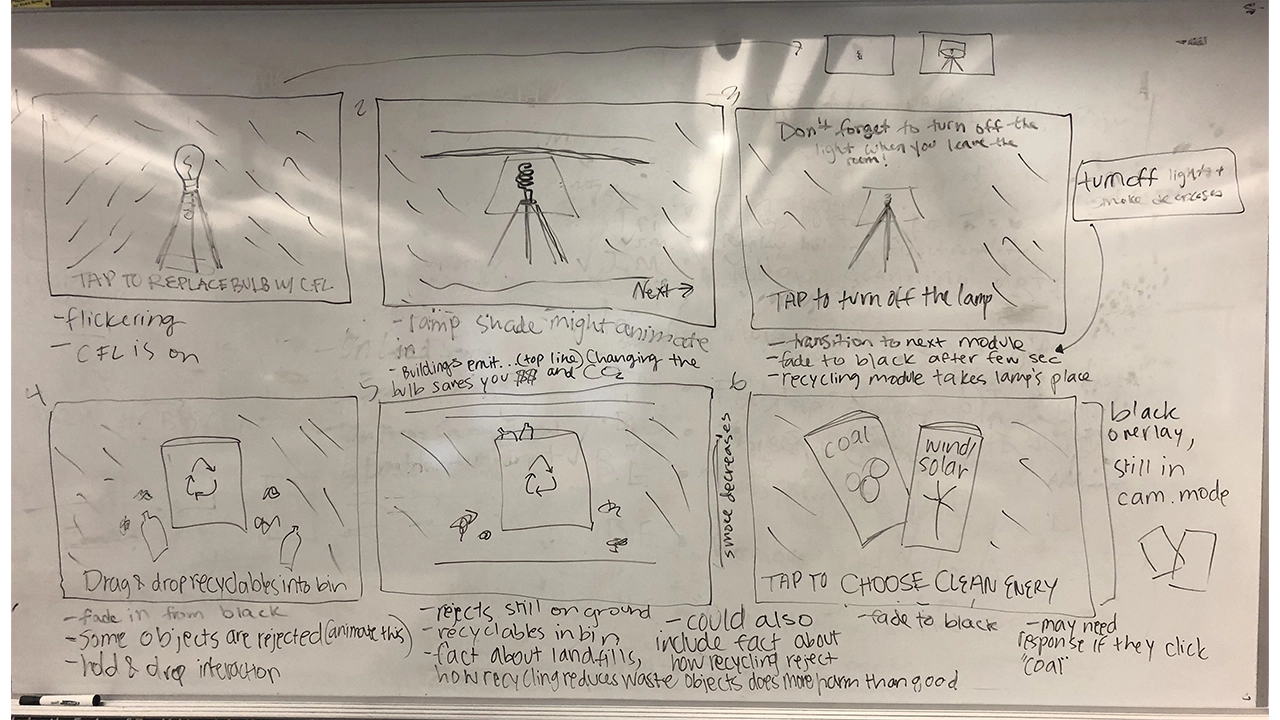

With our failure and lessons learned from the first iteration of our app, we went back to the drawing board to create a more meaningful experience. For our next storyboards we focused on simple household tasks that have a big impact on individuals’ carbon footprints. We presented users with a 3D lamp in their environment surrounded by CO2 visualized by clouds of blackness. In the experience, users are prompted to switch from old light bulbs to energy efficient bulbs, and are informed that using the new bulbs for 1 year is equivalent to having removed as much greenhouse gas pollution as taking 2,000,000 cars off of the road. After, users are reminded that simply switching off the lights when you leave the room will also reduce their CO2 emissions. Each time a task is completed successfully, the clouds of CO2 would decrease. We built this in Unity and tested it with students around Drexel and found this new iteration to be extremely successful. Our success with this module confirmed our theory that people would enjoy a more kinesthetic learning experience. We decided to keep this idea for the rest of the app, and made the decision to break the app up into three “modules” or tasks for users to complete, all of which will help reduce their carbon footprint.

Again, we went back to storyboarding and outlined a module that follows this lamp interaction but places an emphasis on recycling. We found from talking and surveying people in our target audience that not everyone recycles, and this is partly due to people not knowing what you can recycle or not. With this new module you are presented with a recycling bin with a mix of recyclables and trash scattered around. We wanted to gamify recycling, and created a trial and error game shows people what they can and cannot recycle while also encouraging people to think more about recycling an interactive experience. If a user attempts to recycle a piece of trash, it is rejected from the trash can and shown a message saying why the item was rejected. We used physics materials on the trash and recyclables to give a more realistic experience, so when the objects are thrown into the trash it mimics the way the objects would fall if not in an augmented reality experience. We wanted to use these physics materials and the accompanying animations to reinforce that this situation can be replicated in everyday life. This method was very effective, and through usability testing we realized that people did struggle with discerning what is recyclable versus what is not, so this became a very important module.

The final module was intended to have users realize that they could change their energy to a cleaner source such as wind or solar in an easy and convenient way. After meeting with Drexel’s Institute for Energy and the Environment, we learned that one of the best things an individual can do to reduce their carbon footprint is change where they get their energy from. The original storyboard presented users with two pamphlets, one advertising coal and one advertising solar and wind powered energy. Users made their selection, and when they selected clean energy they were given more information on why switching reduces your CO2 emissions and how to switch. This module was very forgettable to users and was the least engaging.

Due to the fact that switching energy sources is one of the most effective ways to reduce your carbon footprint, we needed to fix this. We wanted to create a story for this module because energy consumption has changed so much over the past 200 years so for one last time, we revisited our story boards. At this point, users are shown 3D models of energy sources that society has relied on in the past starting with wood, and followed by gas, coal, and are finally presented with a solar panel and wind turbine. We wanted to show people that these nonrenewable energy sources are a thing of the past, and that clean energy is the future. Users are then prompted to select an energy source. When they select wood, gas, or coal they are shown a message that informs them that there is a cleaner energy source that has does not produce CO2 emissions. When they select wind and solar energy they are then shown how easy it is to switch your energy provider, and are presented with a novel AR laptop that gives a simplified demonstration of how easy it is to switch your energy from coal or gas to solar or wind without having to install anything into your home. After testing this new module, none of our users selected a nonrenewable energy, and were very surprised that switching your energy provider was really that easy.

Designing for AR has proven to be quite different from anything we have done so far because for the first time we are not designing for a screen, we are designing for the world. We have learned that the best AR UI is one that does not interfere with the experience itself unless it directly improved the current view. Interface is still a major factor in AR apps, despite how much it can get in the way, it is crucial to guide users through the app to avoid confusion. As AR is a new technology, most people do not have a mental model for this type interactive experience. A good interface was essential to our project as it will guide users through an experience they are currently uncomfortable with.

For example, instruction text was extremely important. There needed to be readable text that told users where to look and what to tap. Without this instruction text, it is unlikely that users would even get the models placed in the scene. Instruction text occupies the top of the screen and is white with a dark shadow behind it. After testing, users never had a problem reading this text. If there is a major action to be completed, it is communicated at the top of the viewport.

The shock factor of seeing CO2 visualized in your space is accompanied by text to inform users on relevant issues surrounding greenhouse gas emission. We decided to employ dialog boxes throughout the application to display this text. These dialogs are pushed to the bottom of the viewport and tapping anywhere on the screen, rather than just the dialog, progresses through the app. Contrast issues are much more complex in AR. We have no idea what these dialog boxes will be overlaid on. In order to combat this, the background of the dialog boxes are slightly transparent black boxes with white text inside of them. Based on user testing, this boxes are completely readable in all situations.

Finishing a module of the main AR experience unlocks more information about the given topic. We communicated this information using what we call “Learning Layers”. These are large dialog boxes that summarize our scientific research and data surrounding the theme of the specific module. Learning Layers take up only 75% of the screen and use similar styling as the dialogs, they are semi-transparent. This way, users are never fully taken out of the immersion. In the 25% left at the top of the screen there are close and next buttons. The close button is red and accompanied by an X and functionally minimizes the Learning Layer. The next button is accompanied by and arrow and functionally progress through the Learning Layer and transitions to the next module.

The last major interface element is the badges and guide. There are three distinct modules that, upon completion, award badges through the Learning Layer transitions. The badges then stay at the very top of the screen and give people a mental model of progression through the app. All three badges are grayed out until they are earned at the end of modules. The intention behind this was so users are aware of their progress in the app. It also adds a layer of gamification. There is a meaningful congratulatory achievement for completing each module.

The only other instance of interface, besides the Learning Layer, taking up a significant amount of screen space is during the lamp scene where a silhouette of a new energy efficient bulb appears to guide users towards the proper action. This helps users understand they are replacing the old bulb on tap as well as leading users to aim the ray cast properly. This is a great example of development and design working symbiotically.

CO2Black is the result of 6 people, 6 months, and an entirely new realm of 3D application development that nobody had experience working with. We came together with the hope that when people used our app, they would walk away with the belief that their actions have a direct impact on the amount of carbon dioxide in the environment. We are unable to quantify success due to this, but our qualitative metric of success depended on how people felt after going through the app, and our users found the experience fun and engaging, and felt that the experience was much more interactive than just reading a pamphlet about carbon dioxide. With these aspects in mind, CO2Black is a success. One user said after experiencing when going throughout his day, when he would traditionally throw away his morning coffee he went out of his way to recycle it. This result is exactly what we were striving for. We broke CO2Black down into three modules that had everyday tasks in hopes of them influencing their everyday actions.

The last six months was an incredible learning experience for our whole team. We learned that an agile approach is the best approach for this. This is a new technology that not many people have experience with, so it is a delicate balance between pushing the boundaries of the technology and defining interactions that people are comfortable using. We had the special task of not only trying to teach people about CO2 and the impact of their actions, but we also had to teach them how to use AR, usually for the first time. This was a particularly difficult task because we ourselves were learning how to design and develop using AR for the first time. Using AR for the sake of using AR is a lesson that we quickly learned was not the best idea. We wanted to use AR to enhance your experience, and we kept this mindset throughout the development of CO2Black. We found out through user testing that giving instant feedback, whether that is through animations, UI, color, or haptic feedback is very important to show the cause and effect of actions. Lastly, a solid team is one of the most important aspects of a successful project. We were able to depend and rely on each other and that sense of security allowed us to take risks in our ideas and development process.

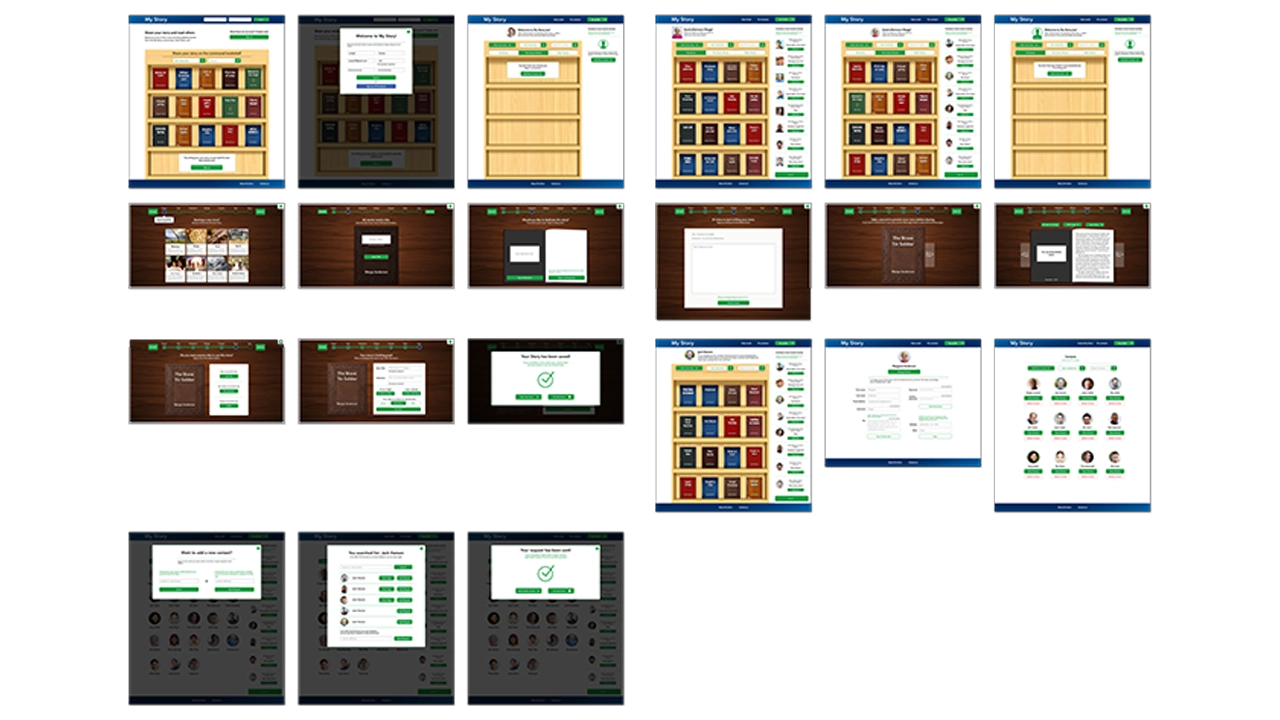

My Story is a website designed specifically for senior citizens to create and share stories on. These days the world is more connected than it’s ever been, but often times as designers we don’t take into consideration the challenges the elderly face when dealing with technology. Our goal with My Story was to create a platform that anyone could use no matter their age or tech capability. Of course we acknowledge that in order to create a successful product, you must have a specific audience to target, but we figured if at the very least we could get seniors to understand the flows, than anyone could. Part of our success in doing this was our focus on creating skeuomorphic elements that users could easily identify with, like the ‘Bookshelf’ or the ‘Story Viewer’. By incorporating skeuomorphism and applying our research in design for the elderly we were able to create a site that users could sign up for and share stories from.

My Story was one of many ideas pitched at the beginning of our junior year’s workshop class. Everyone was tasked with coming up with an idea for a website or an application that a team could develop in six months, and My Story was one of the ideas selected. After voting and choosing who would do what, My Story ended up with three members, each with a set of skills and strong suits.

Seniors are often overlooked as users of technology because a majority of the world has written them off as people who either have no business using technology or simply don’t believe that they’re equipped to understand it. Therefore their needs don’t get taken into consideration. While it is true that there are seniors out there that have no interest in joining the world online, it is still our job as designers and problem solvers to create user friendly solutions for everyone, not just the people who know it best.

So it was our mission to create something that could be easily understood by those who are not as familiar with the inner workings of technology.

From the very start we knew this would be an iterative, intensive process; if we were going to be designing for an audience that we personally had never addressed, we needed to understand how they thought, and the best way to do that was by actually meeting with them. Thus it was crucial that early on we made a connection with a senior center where we could go and do consistent usability testing.

It was clear from the start that whatever we designed needed to be backed up with thorough research and testing. What this meant for the team was that we needed to really dive in and understand technology from a seniors point of view. Since we didn’t have easy access to our target audience, we had to get creative when it came to gathering our research, so we tackled it in a few different ways.

The first thing we needed was a proof of concept…would people actually use this? What would people use it for? Why would they want to use it? How often would they use it? What other sites do they use? What would they be willing to share?

To answer these questions we needed a survey that we could send out to the masses, so we turned to our favorite free survey tool: Survey Monkey. Using the questions above we were able to gather over 60 responses, and as a result we found that there is a demand for My Story and people reported they’d use it.

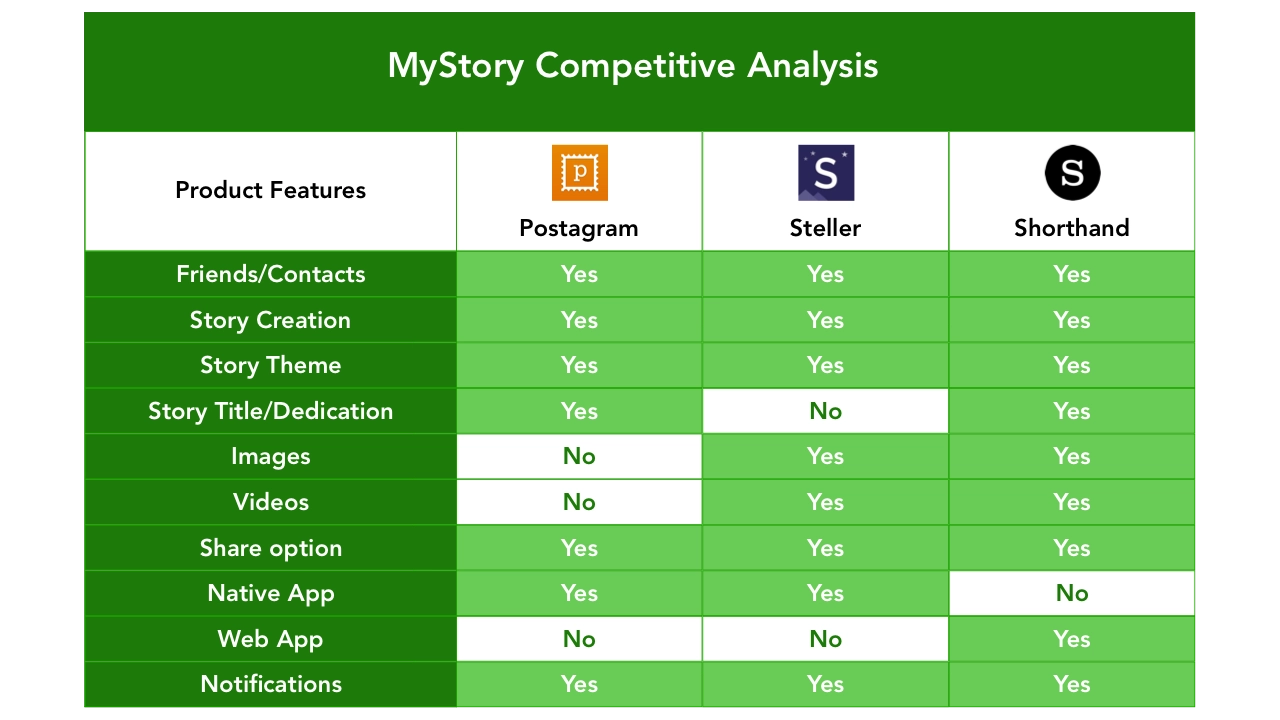

Since there were already successful sites out there with similar concepts to My Story, we decided to do a competitive analysis to figure out what features we wanted on our site, and what features we could do without.

Before we could jump into any kind of design we needed to understand the challenges seniors face when it comes to interpreting content displayed on a web page, so a lot of our research was focused around text legibility and color contrast.

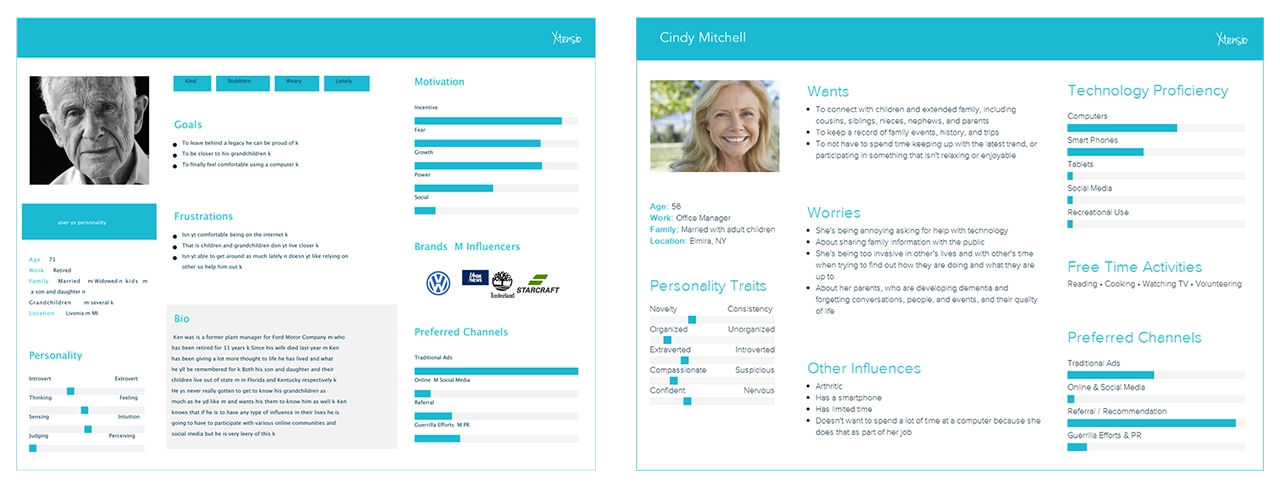

Once we had a solid understanding of how to design for seniors, and what exactly we wanted to include on our site in terms of features, we needed to come up with a few user personas that we could refer to as we began creating the site.

Target audience (60+ age range) & Secondary audience (40-60 age range)

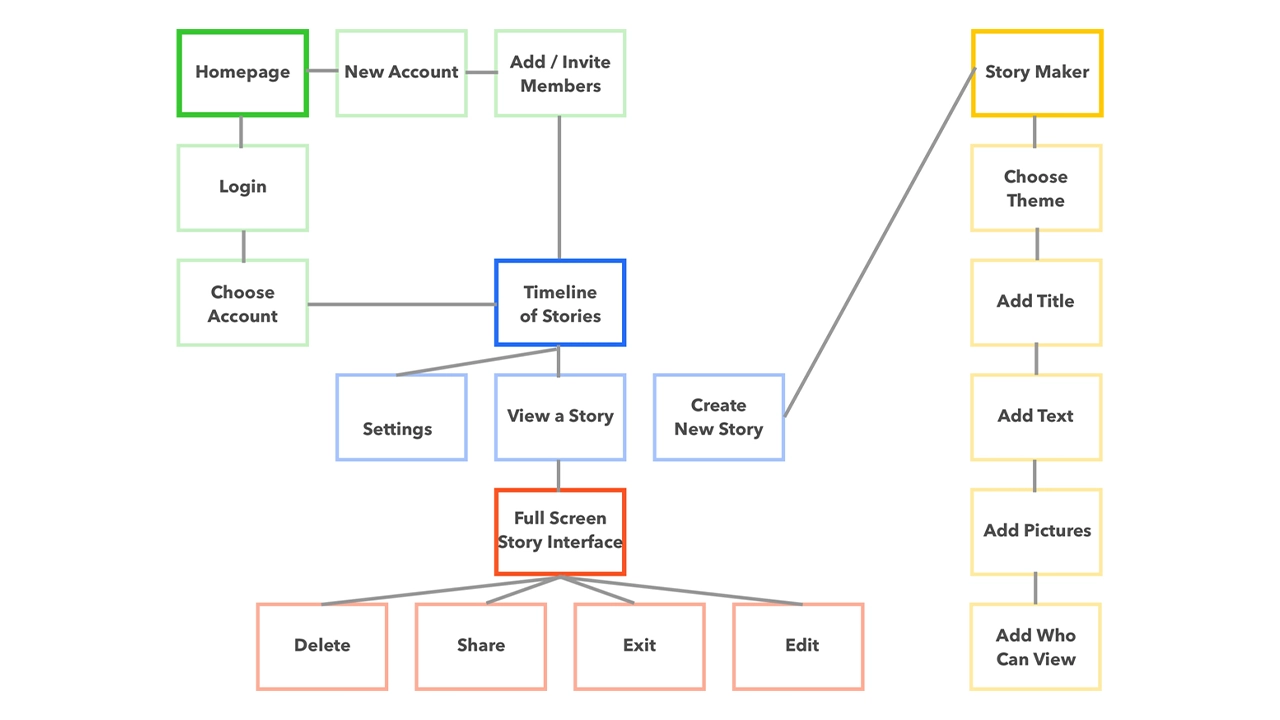

After defining the functionality of our site, and the different pages we wanted to include, we created a site map in order to understand how users would navigate from page to page. This came in handy as it gave us an overview of how the site would work, and where users could go depending on where they were on the site. Our goal was to make every single page accessible with three clicks or less, and the sitemap helped us visualize what that would look like.

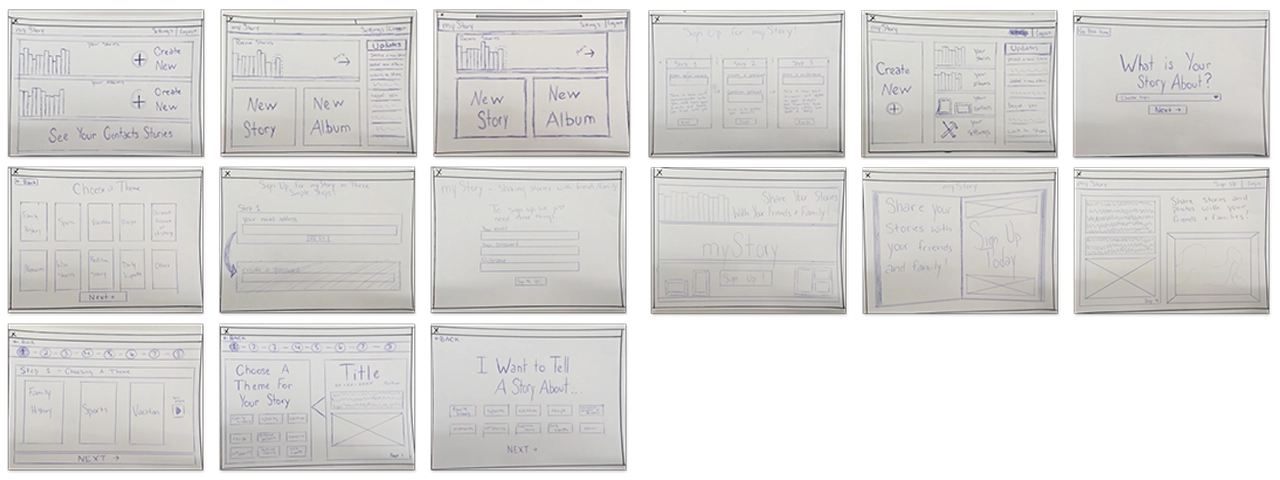

Before we could start designing our interface on the computer we needed to brainstorm all the possible ways we wanted to display the content. Using pencil and paper, we were able to come up with many different concepts that we could quickly cover.

Tools

All sketches were done with good old fashion pencil and paper.

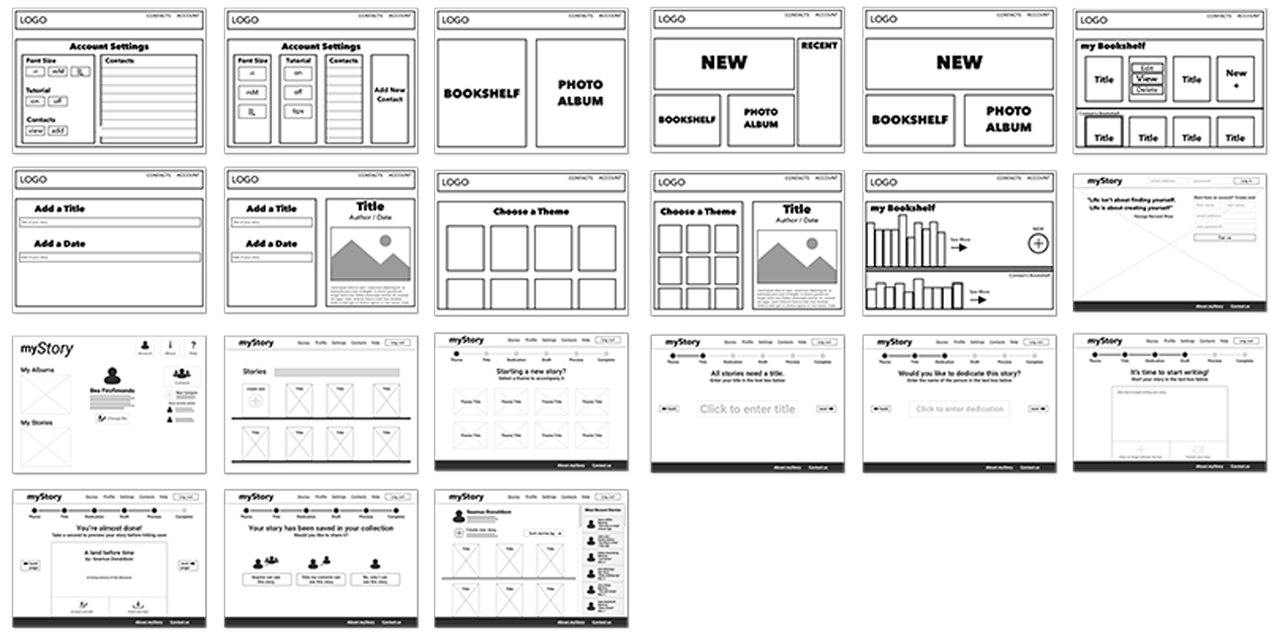

Now that we had a solid foundation for the design of the site, we jumped into sketch and began wireframing.

Tools

Low fidelity screens were created in Sketch and Adobe Illustrator.

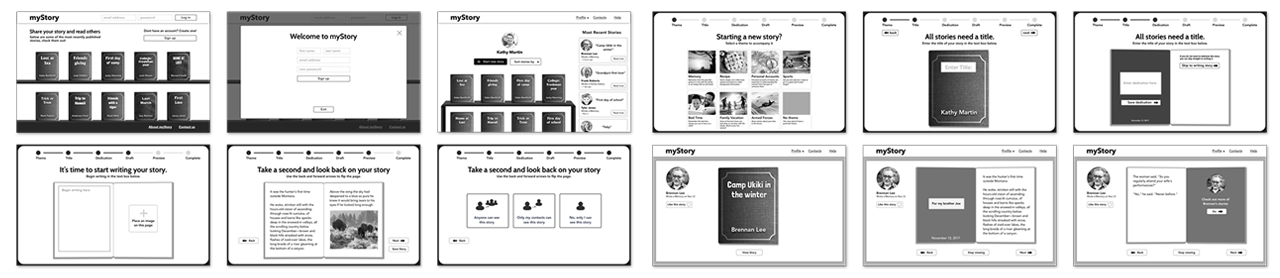

After showing our class the progress we had made with the wireframes, we got feedback and decided on a layout that we could then refine and begin to stylize. Using the research we had done on fonts, we decided on ‘Cabin’ as our main font, and used it across the site with varying weights. We also brought in images and reworked the UI based on the feedback we got during critique.

Tools

All mid-fidelity screens were created in Sketch, then copied and pasted into Adobe Experience Design. Using XD we were able to create a flow connected by premade slide transitions. This wasn’t used for testing because it was too low-fidelity. We put it together so that we could better understand the flow of our story creation process.

At this point we had all the screens designed and were ready to implement colors and images across the site.

Tools

All high fidelity screens used in the prototype were exported from Sketch using the Flinto plugin. We were then able to manipulate the elements in Flinto to create links between pages using custom animations.

For two weeks we performed usability testing with both the primary and the secondary audiences. Each of us showed off the prototype, and explained to testers before they started what the site was about, and what the main features were. We also explained that they were testing with a prototype and some things may not be perfect. After we did our introduction we let them click through while asking them to complete certain tasks. Throughout testing we took notes, which we then reflected on as a team when we got back together.

At first we were a little bit worried about accomplishing all the things we wanted our site to do, in code. For a three person team, it seemed like a lot and with only three months left we knew we had to hit development hard. What we had promised for the final was a website that a users could create an account on, add contacts, share stories, and customize stories by theme. Not to mention the challenges we would have creating all of our elements with skeuomorphic styles… we had a lot to tackle but tackle it we did.

The first thing we did was a ton of research. Because none of us had ever created a website with such a laundry list of features, we were for the most part going in blind. Quickly we realized that WordPress would be the most sensible place to start because it was built for content management and our site had a lot of it. We also decided that we would start with the ‘twenty sixteen child’ theme because it was already organized and had page templates for things we would need to eventually build ourselves.

We then turned to the Ultimate Member plugin which seemed to solve all of our problems when it came to accounts and friends, but it also came with a set of challenges that sometimes slowed development. Without Ultimate Member we would have had to create a database from scratch that could store account info, request friends, and save stories. That said, Ultimate Member is also an extremely robust plugin so in order to target certain elements in PHP or CSS it took some digging.

The other challenge was creating a custom animation that would naturally resemble a page flipping in a book. Luckily we found a script in a jQuery library called booklet, and just brought it into our code and customized it to fit our needs.

With all the research that we had done, we had a pretty good idea how to accomplish our goals so week after week, we just knocked items off our needs and wants list until we were down to our wants. The site was initially set up using a WordPress child theme called ‘Twenty Sixteen’. This gave us a solid foundation to start on. From there we began styling the home page. Since we wanted to create a minimum viable product as soon as possible for testing, we started with the skeuomorphic bookshelf on the home page. We used mix-it-up and a grid system to create the books and brought our bookshelf in as a background that could be populated.

Our next step was implementing Ultimate Member. We started by getting account sign up working, and then moved on to adding friends. This was the easy part. The true challenge was how we were going to store the data specific to those accounts, and how we would be able to create share options based on the decisions users make.

The next step was creating a taxonomy for our theme,s which would bring in a book cover style as well as a unique title text. We did this by pulling the category data and assigning a corresponding class, which would then display selected theme styles.

Once we had reached a point in development where our live site had the core functionalities of creating accounts, posting stories, and viewing stories, we decided to begin testing. The reason we chose to use the live site instead of the prototype was so users could then make their own decisions and become familiar with the flow. We also shifted our focus from design to development and a majority of our UI changes were reflected in the live site as opposed to the prototype.

It has been incredible to see a vision like My Story turn into a reality. Over the past six months we’ve taken a concept from nothing to a fully fledged website and we couldn’t be more proud of the work we’ve done. While we haven’t gotten every last thing fine tuned and styled, we were able to knock everything off our needs list, and we are successfully delivering on what we’ve promised. If we were to take this to the next step, we would implement some type of social media login, potentially allow for sharing on social platforms; we would also find a way for authors to include images in their stories, and would look to refine the skeuomorphic elements even more to create that feeling of a real book. All in all, My Story has been an amazing experience for all of us, and from the testing to the debugging, we’ve learned a lot.

IDM362: Interactive App Design II by Kristen Rehm

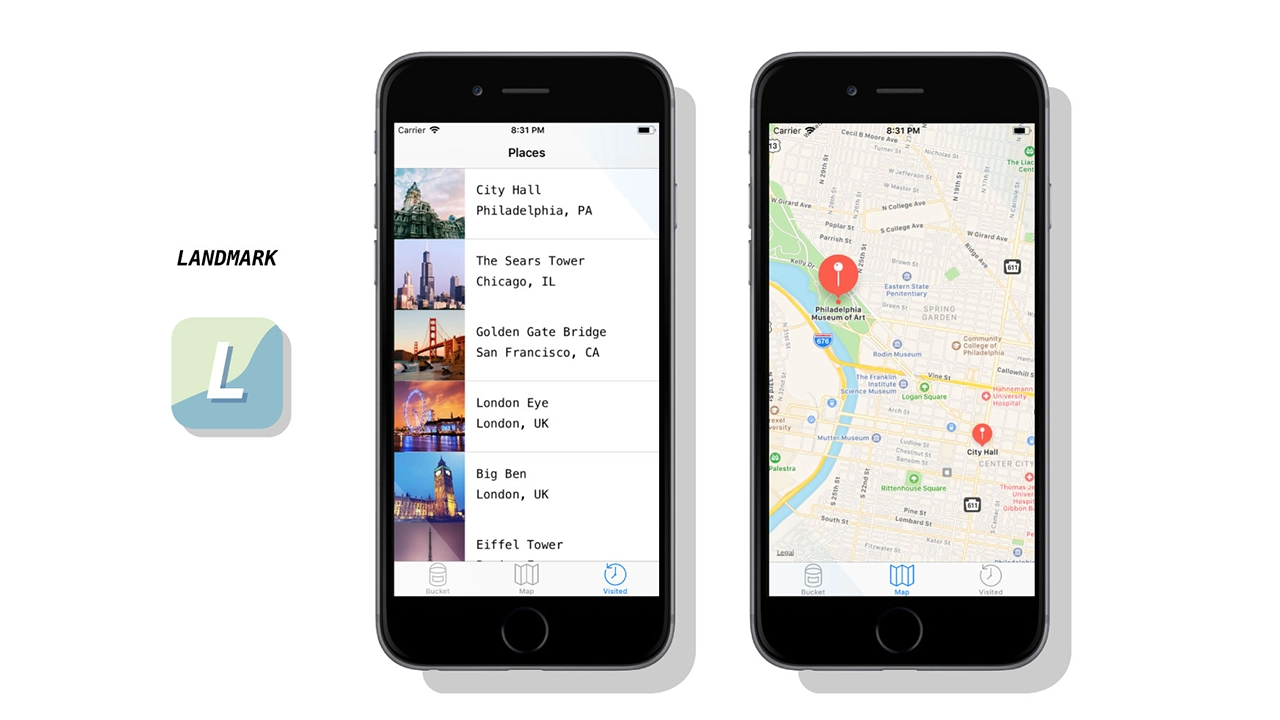

Simply put, Landmark is a travel companion application. But it’s also much more than that. The idea for Landmark originated as an AR application – one where a user could pick up 3D collectables once they’re at a physical tourist attraction. However, time (and knowledge) constraints left me condensing the idea into a tracking application instead. Landmark allows its users to track the tourist attractions they’ve visited, and create a bucket list of the ones they want to visit next. It features an interactive map, where users can explore the city they’re in, and see the popular spots to visit within.

This app was created with the intention of solving a problem – the cluttered camera roll. Oftentimes people who frequently travel, document their experiences by taking lots of photos on their mobile devices. But there isn’t a satisfying way to track where you’ve been, or what you’ve seen while traveling. Sure, you can scroll through vast amounts of pictures to finally find your selfie with Mount Rushmore – or you could use Landmark to document the experience, have it conveniently saved in one location, and to find new places you’d like to go next. Landmark is designed specifically to inspire it’s users to add to their bucket list.

Creating a native app for the first time meant a lot of challenges – aside from learning the ins-and-outs of xCode. One of those was discovering a solid task flow from screen to screen; what did users want to see first? Were they more interested in the map or the bucket list? The places they’ve already visited, perhaps? This led to user testing, which helped me solve some of these problems upfront. But as with any project, more roadblocks – and need for iteration – came after.

While creating Landmark, there were some ideas that I had to scrap. I originally was going to have a search feature for different cities and locations, thinking this would be the best way for people to discover new places for their bucket list. However, I found that users typically already have an idea in mind of where they’re going next – or want to go. Rather than having search functionality, I created an add button that allowed users to input their own locations and landmarks. This allows for more customization, and a more personalized experience.

Landmark helps users record where they’ve been, when they visited a famous tourist location, and keep track of what they want to see next. It provides a unique space for this task, and is a great application for anyone who wants to travel more, document their experiences, or see what else is out there that they might’ve missed. I ensured the task-flow was simple and straightforward — there’s nothing more stressful and frustrating than not understanding how an application works. It might be simple in nature, but this really allows users of Landmark to take it and run with it. After several uses, Landmark becomes a reminiscent journal of sorts – one where you can enjoy the things you’ve done and seen, and look forward to the future and what’s next.

Despite being unable to create all that I envisioned, I think Landmark is absolutely a success. I wanted an app that users could keep returning to in order to track where they’ve been, and I’ve successfully created that. While additional features, such as AR collectables, gamification, etc would have been added bonuses, Landmark serves it’s original purpose, and serves it well. That being said, I am incredibly happy with the outcome of this app, and would enjoy working on it more in the future to live up to the higher potential it has.

Brendan Luu & Brendan Russo

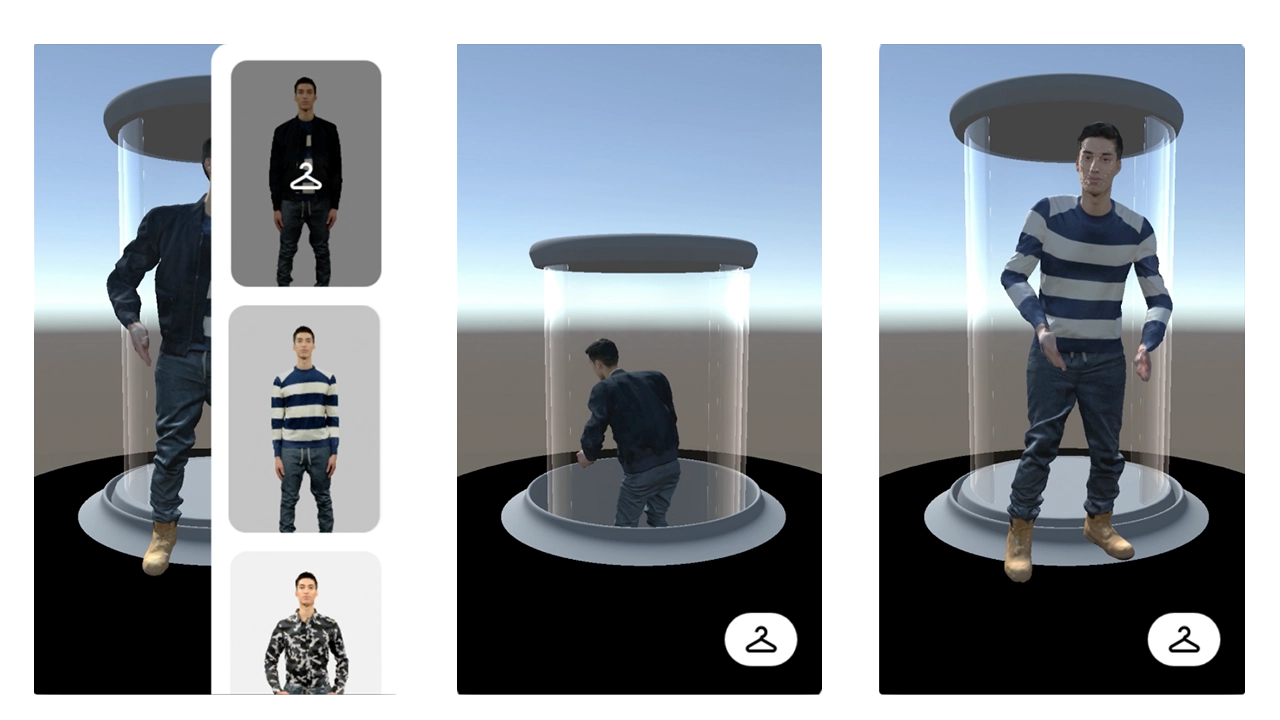

We used the structure sensor, an IR 3D scanner attachment for the iPad Pro, to scan photo-realistic mesh of clothing on a model.

We then placed the 3D models into augmented reality using Apple’s ARkit, a framework released last year that unlocks depth sensing technology into iOS 11 devices.

Online shopping has changed the retail industry, that is undeniable. We believe AR is an upcoming technology.

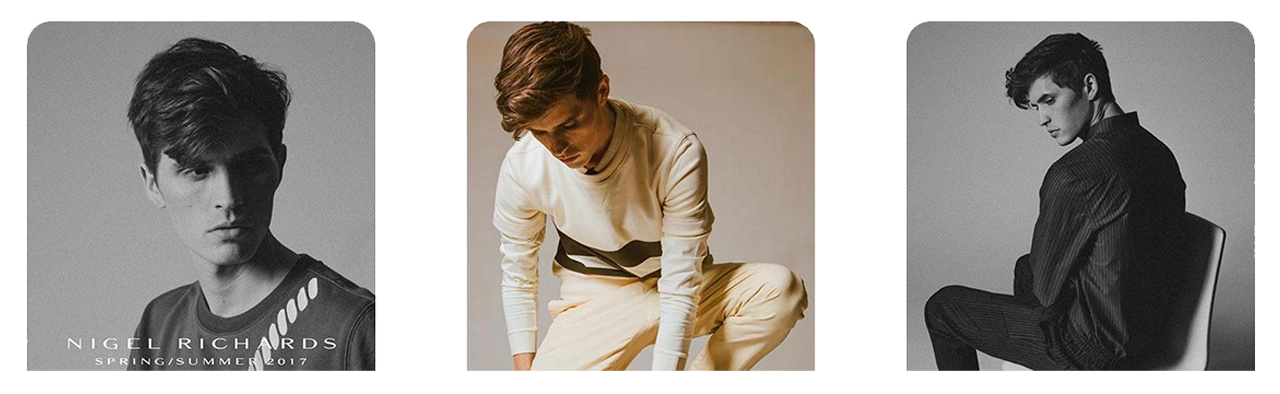

Communicating brand identity means a lot more than just staying within design guidelines and displaying styled outfits. We have set out to help tell the story of Nigel Richards. Our storytelling approach enlists elements such as motion, pose, mood, and flow in addition to the standard aesthetic decisions. AR allows us to attach a meaningful story to the product more so than in a traditional retail experience.

Lookbooks have been around for decades but have barely evolved. It makes sense, they’re an industry standard and there has been a proven best way to do it. We believe the goals of a lookbook; again promoting the brand, communicating pricing to buyers, and gathering a collection, can all be done more effectively in AR.

After speaking with the Design and Merchandising faculty from Drexel’s Westphal College, we identified a few different types of people that would benefit from seeing clothes in AR. First, millennial shoppers who purchase clothing online.

Younger shoppers are more aware of new tech and more comfortable with AR so are a good audience for us to target with this app.

We believe millennial shoppers would be a strong group of “early adopters” of this kind of retail. This will help open other groups up to such technology.

The D&M faculty also said that fashion designers could use this app to display their clothing at retail expo’s where hauling physical merchandise is often difficult to manage. These types of environments also don’t lend themselves to communicate branding and mood like this app could potentially do.

We took inspiration from Nigil’s Spring/Summer lookbook, we liked his clean and modern aesthetic. We also looked towards physical retail for inspiration for how clothing is displayed in stores today.

We really liked the idea of displaying one look at a time and making it the highlight of the environment, similar to a true fashion show experience. The idea of revealing clothing by coming up from the ground was inspired by Louis Vuitton’s runway show where models arrived out of elevators.

We also identified Paul Smith as a similar designer brand with established aesthetics. The concept of the elevator was also inspired by his use of capsules for window merchandising.

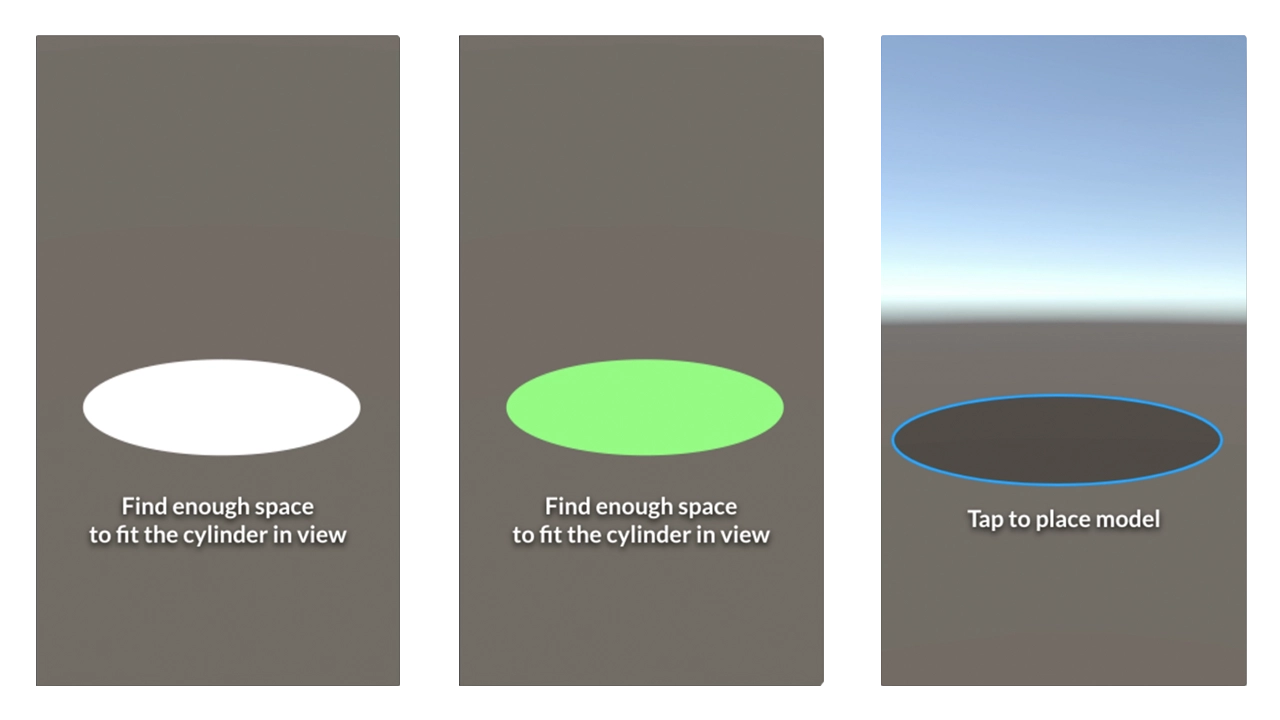

Ask user for them to find enough space to fit a circle in perspective that will measure the same as our unity scaled scene. This way we know they will have enough space for the scene.

Tapping the screen when you think there is enough room will confirm that step.

Scanning would then begin. Once complete users would be asked to tap within a blue circle that mimics the size of the initial circle to place the scene.

Orange square will show up where users tap within the placing circle. This is the scene placed. The empty elevator tube is now visible.

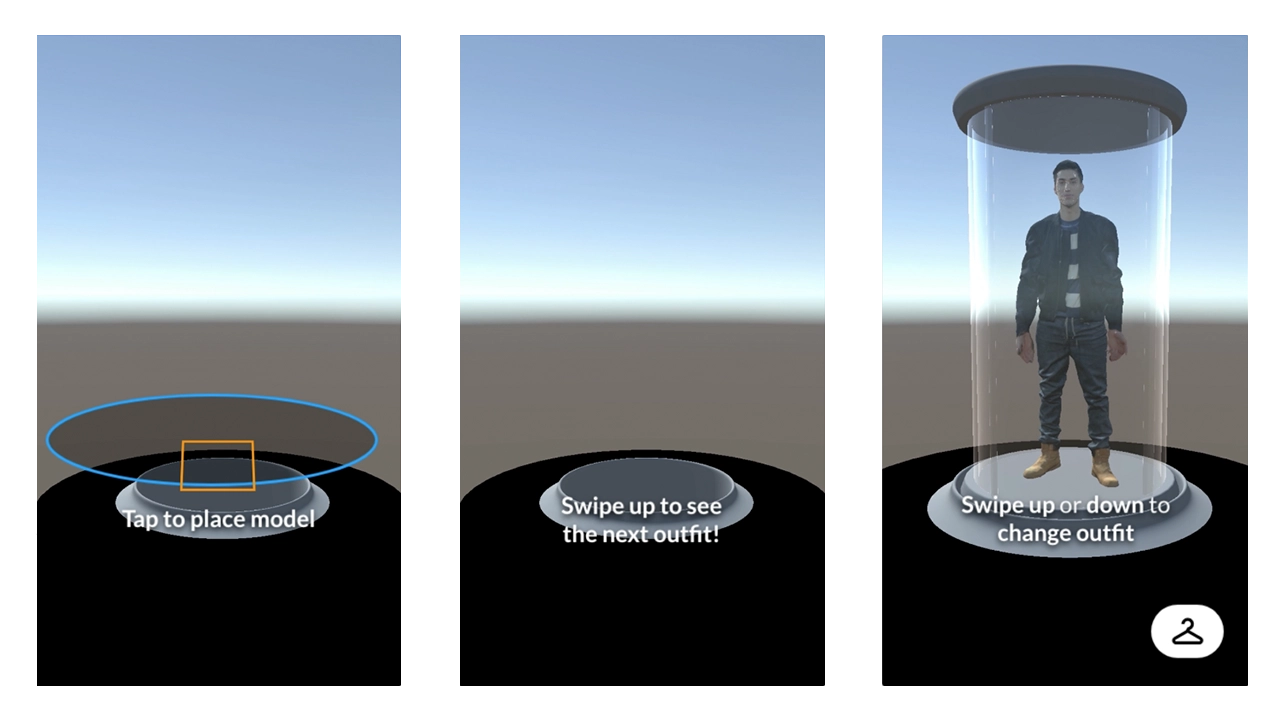

Users are then encouraged to swipe upwards to view the first model in the set. This is to try and enforce the mechanics of the app. We want users to be able to simply swipe through the app, up and down, to view different looks.

The rack button is now visible as the model comes into view. The swipe up or down text comes into view and fades out after a few seconds.

Model walks out of the elevator and starts motion, dancing in this case.

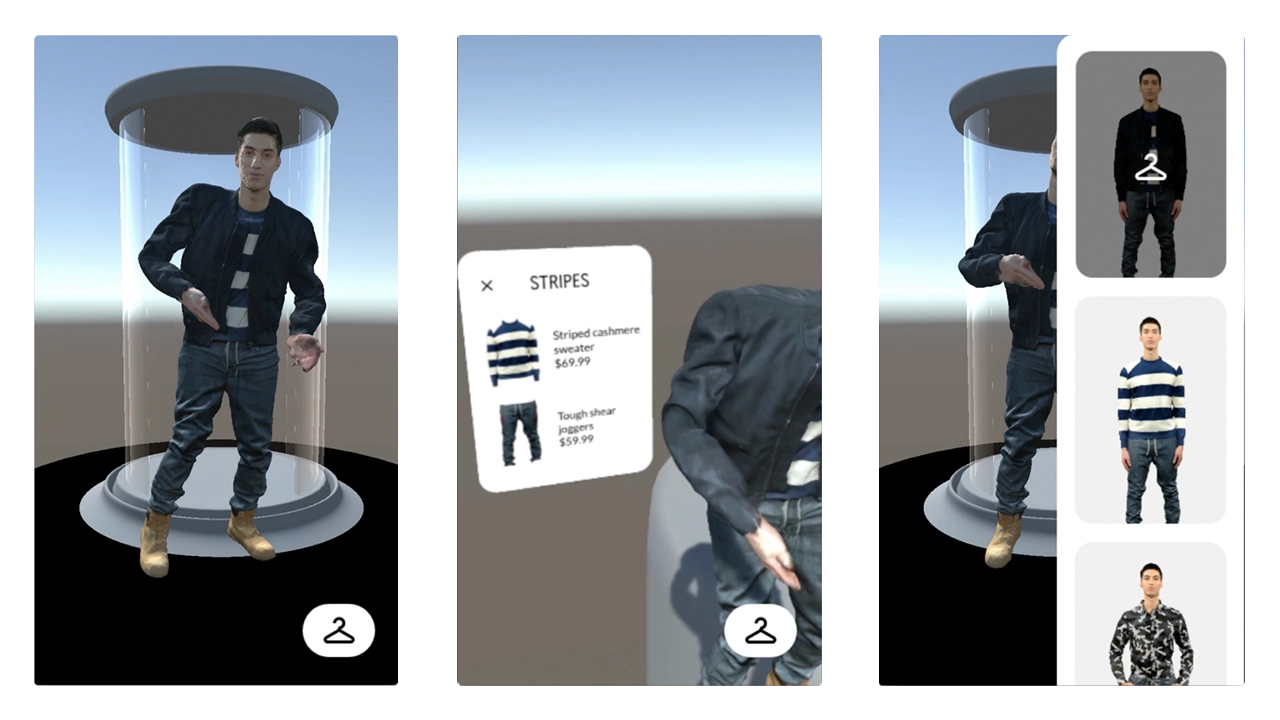

Tapping the model brings this AR interface up that describes the outfit in more detail. Tapping the X on this interface closes it.

Tapping the rack button brings this rack view in from the side. This list scrolls and tells you what outfit you are currently viewing. Tapping outside the rack view boundary will close the view.

When rack view is up, tapping a thumbnail will bring up said outfit from the elevator.

When changing outfits, the model will walk back into the elevator and go back down.

Once the old model has gone down, the newly selected model will rise up.

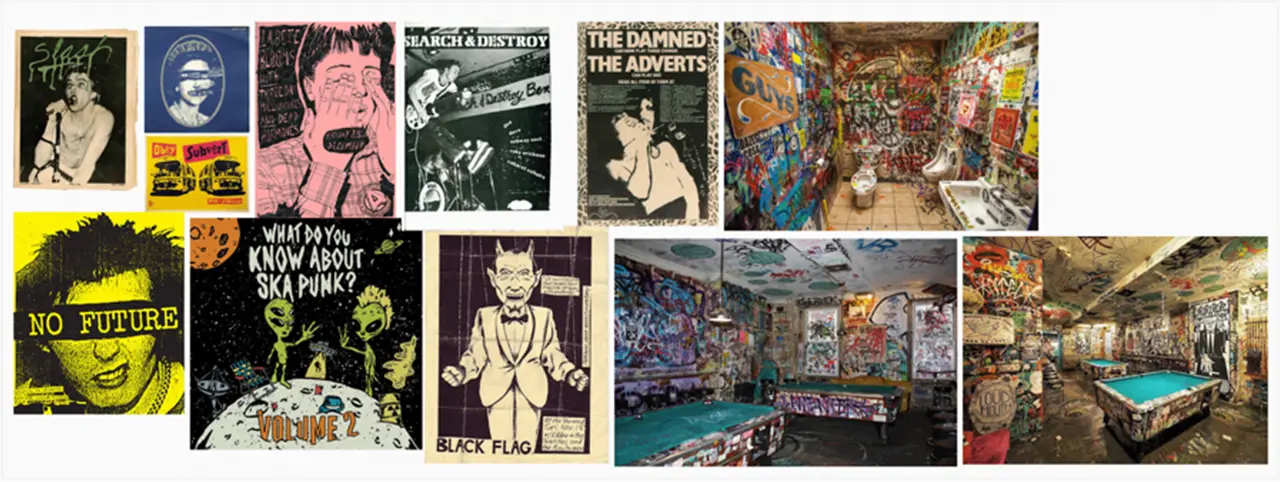

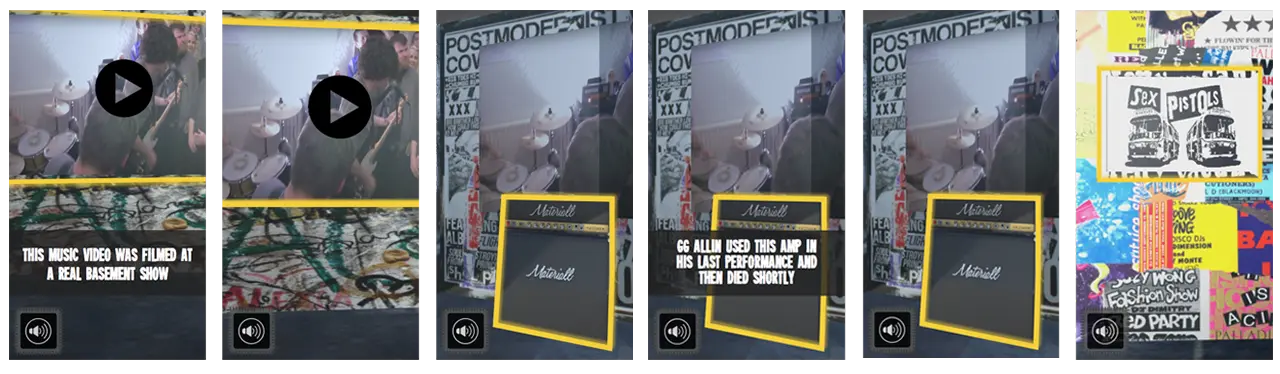

This project was created by combining the ideas of wanting to recreate what it is like at a house show / punk concert in a 3D space and as well try to use augment reality to fully surround a user in visuals via a faux portal.

These two concepts were brought together and the result is The Basement Exhibition.

Jake Bender & Jake Culp

With these goals in mind and the short time frame we were given, it was crucial to immediately start development and begin wireframing and creating moodboards so we could see how the application would look and run.

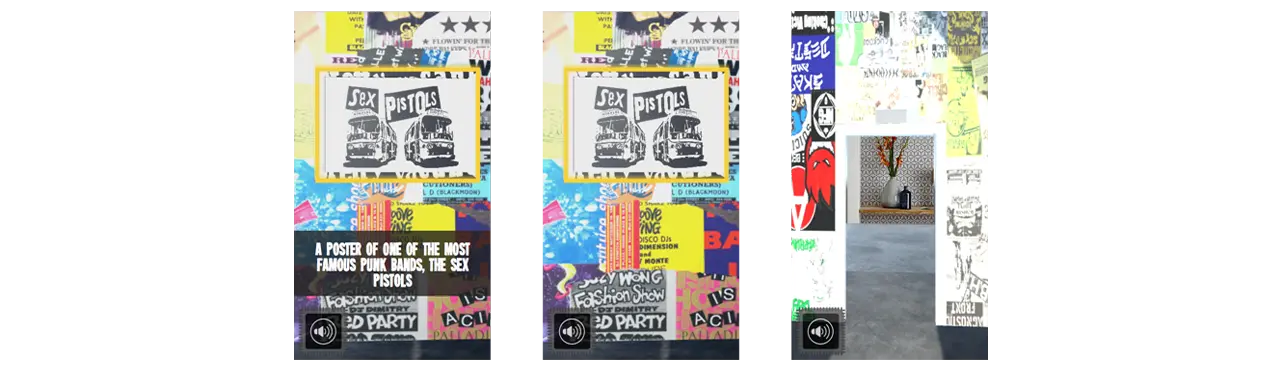

Before creating a moodboard and wireframes, we needed to identify who exactly our audience was. We determined that the majority of users would be between the ages of 13-21 and would have some sort of punk music background. These meant moving forward we needed to heavily focus on incorporating the punk aesthetic into our design layouts.

We took inspiration from old punk flyers, posters, and zines that we had collected online. We noticed after awhile that the punk aesthetic was very jarring and in your face. The colors were very bright and text would sometimes be placed directly over images without the thought of design in mind. We drew so much inspiration from these pieces of art and wanted the experience we were developing to really allow for the user to see up close and in detail these pieces of art.

To create the application we used Unity game engine along with Apple’s ARKit to allow for the user to place their exhibition wherever they want.

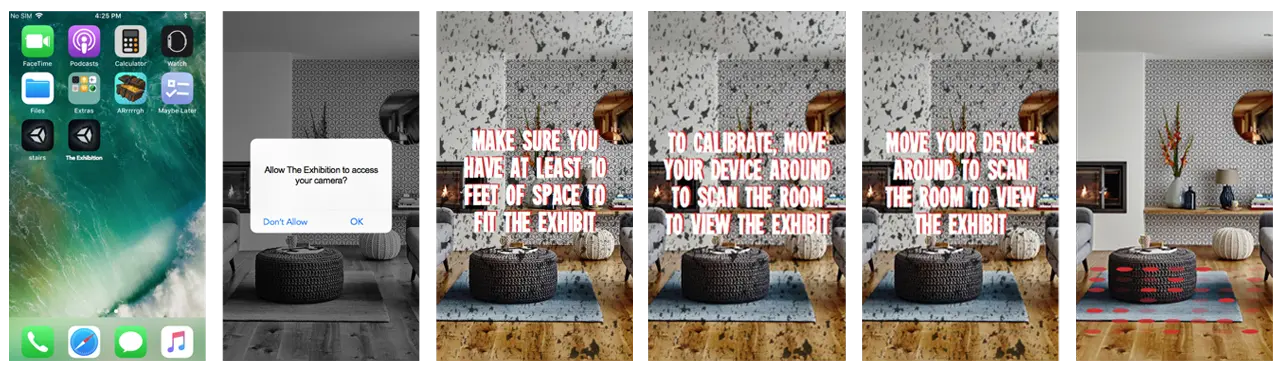

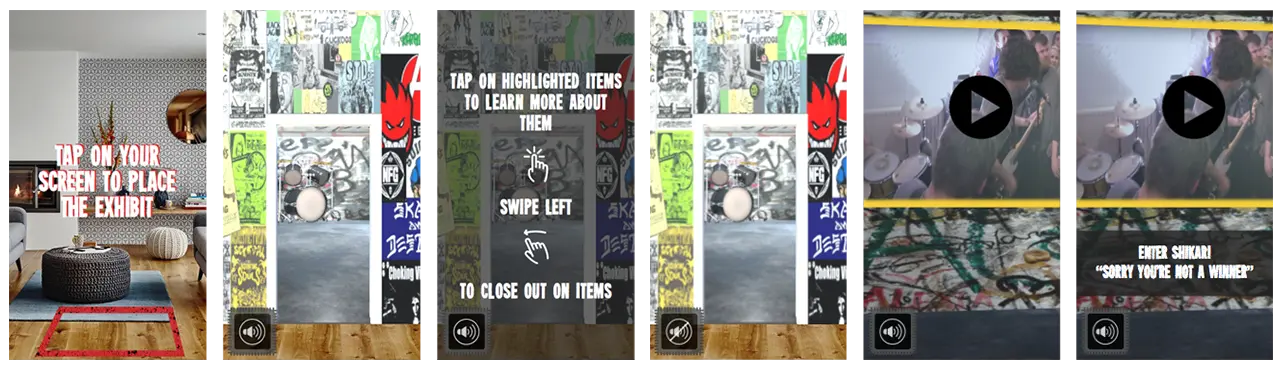

To allow for the user to simulate a teleportation into a new world we had to implement custom shaders and materials into our Unity project. This was our biggest challenge with getting this functionality up and running. Once this process was complete the rest was creating the room in Unity and refining the details of the user interface.

When it comes to the design of the user interface, we wanted for the setup process to be easy as possible for the user. This is due to the fact that the biggest impact the application has on the user is done after they have finished setup.

Keeping our punk aesthetic and moodboards in mind, we decided to have a simple layout of steps that the user would complete in order to properly place their exhibit.

Once the user has properly placed their exhibit, they are prompted to then walk through the portal and be seemingly taken into a different world. This world has the feel of being in a basement where a punk show is about to take place. Along the walls of the basement are posters and flyers that the users can view and look at.

As well, there are future goals to implement interactive objects and videos in the basement space. Users could then tap onto the items to learn more about them. This gives the users more ways to interact with the exhibit and can create a more long lasting and enjoyable experience.

A huge takeaway from this project is seeing how much 3D objects can really help sell an augmented reality experience. Seeing the graphics that we had implemented into the design of the basement in AR made them seem almost life like and we think that they alone could have been enough to fully immerse a user into the exhibit.

IDM231: Scripting for Interactive Digital Media I

By Sarah Bray – 2018

IDM231: Scripting for Interactive Digital Media I

By Joseph Lunine – 2018

IDM231: Scripting for Interactive Digital Media I

By Clay Tercek – 2018